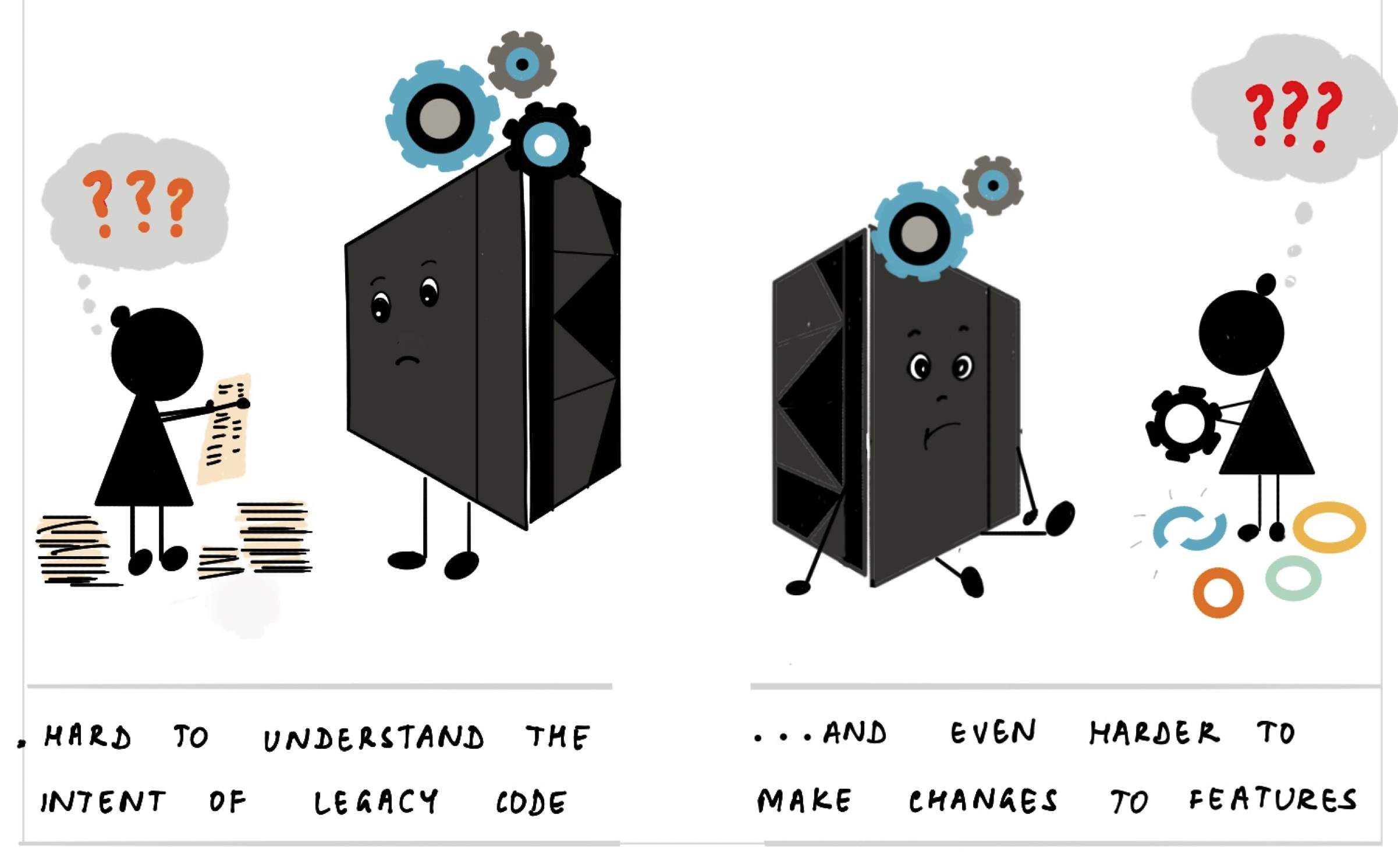

Gitanjali Venkatraman does wonderful illustrations of complex subjects (which is why I was so happy to work with her on our Expert Generalists article). She has now published the latest in her series of illustrated guides: tackling the complex topic of Mainframe Modernization

In it she illustrates the history and value of mainframes, why modernization is so tricky, and how to tackle the problem by breaking it down into tractable pieces. I love the clarity of her explanations, and smile frequently at her way of enhancing her words with her quirky pictures.

❄ ❄ ❄ ❄ ❄

Gergely Orosz on social media

Unpopular opinion:

Current code review tools just don’t make much sense for AI-generated code

When reviewing code I really want to know:

- The prompt made by the dev

- What corrections the other dev made to the code

- Clear marking of code AI-generated not changed by a human

Some people pushed back saying they don’t (and shouldn’t care) whether it was written by a human, generated by an LLM, or copy-pasted from Stack Overflow.

In my view it matters a lot – because of the second vital purpose of code review.

When asked why do code reviews, most people will answer the first vital purpose – quality control. We want to ensure bad code gets blocked before it hits mainline. We do this to avoid bugs and to avoid other quality issues, in particular comprehensibility and ease of change.

But I hear the second vital purpose less often: code review is a mechanism to communicate and educate. If I’m submitting some sub-standard code, and it gets rejected, I want to know why so that I can improve my programming. Maybe I’m unaware of some library features, or maybe there’s some project-specific standards I haven’t run into yet, or maybe my naming isn’t as clear as I thought it was. Whatever the reasons, I need to know in order to learn. And my employer needs me to learn, so I can be more effective.

We need to know the writer of the code we review both so we can communicate our better practice to them, but also to know how to improve things. With a human, its a conversation, and perhaps some documentation if we realize we’ve needed to explain things repeatedly. But with an LLM it’s about how to modify its context, as well as humans learning how to better drive the LLM.

❄ ❄ ❄ ❄ ❄

Wondering why I’ve been making a lot of posts like this recently? I explain why I’ve been reviving the link blog.

❄ ❄ ❄ ❄ ❄

Simon Willison describes how he uses LLMs to build disposable but useful web apps

These are the characteristics I have found to be most productive in building tools of this nature:

- A single file: inline JavaScript and CSS in a single HTML file means the least hassle in hosting or distributing them, and crucially means you can copy and paste them out of an LLM response.

- Avoid React, or anything with a build step. The problem with React is that JSX requires a build step, which makes everything massively less convenient. I prompt “no react” and skip that whole rabbit hole entirely.

- Load dependencies from a CDN. The fewer dependencies the better, but if there’s a well known library that helps solve a problem I’m happy to load it from CDNjs or jsdelivr or similar.

- Keep them small. A few hundred lines means the maintainability of the code doesn’t matter too much: any good LLM can read them and understand what they’re doing, and rewriting them from scratch with help from an LLM takes just a few minutes.

His repository includes all these tools, together with transcripts of the chats that got the LLMs to build them.

❄ ❄ ❄ ❄ ❄

Obie Fernandez: while many engineers are underwhelmed by AI tools, some senior engineers are finding them really valuable. He feels that senior engineers have an oft-unspoken mindset, which in conjunction with an LLM, enables the LLM to be much more valuable.

Levels of abstraction and generalization problems get talked about a lot because they’re easy to name. But they’re far from the whole story.

Other tools show up just as often in real work:

- A sense for blast radius. Knowing which changes are safe to make loudly and which should be quiet and contained.

- A feel for sequencing. Knowing when a technically correct change is still wrong because the system or the team isn’t ready for it yet.

- An instinct for reversibility. Preferring moves that keep options open, even if they look less elegant in the moment.

- An awareness of social cost. Recognizing when a clever solution will confuse more people than it helps.

- An allergy to false confidence. Spotting places where tests are green but the model is wrong.

❄ ❄ ❄ ❄ ❄

Emil Stenström built an HTML5 parser in python using coding agents, using Github Copilot in Agent mode with Claude Sonnet 3.7. He automatically approved most commands. It took him “a couple of months on off-hours”, including at least one restart from scratch. The parser now passes all the tests in html5lib test suite.

After writing the parser, I still don’t know HTML5 properly. The agent wrote it for me. I guided it when it came to API design and corrected bad decisions at the high level, but it did ALL of the gruntwork and wrote all of the code.

I handled all git commits myself, reviewing code as it went in. I didn’t understand all the algorithmic choices, but I understood when it didn’t do the right thing.

Although he gives an overview of what happens, there’s not very much information on his workflow and how he interacted with the LLM. There’s certainly not enough detail here to try to replicate his approach. This is contrast to Simon Willison (above) who has detailed links to his chat transcripts – although they are much smaller tools and I haven’t looked at them properly to see how useful they are.

One thing that is clear, however, is the vital need for a comprehensive test suite. Much of his work is driven by having that suite as a clear guide for him and the LLM agents.

JustHTML is about 3,000 lines of Python with 8,500+ tests passing. I couldn’t have written it this quickly without the agent.

But “quickly” doesn’t mean “without thinking.” I spent a lot of time reviewing code, making design decisions, and steering the agent in the right direction. The agent did the typing; I did the thinking.

❄ ❄

Then Simon Willison ported the library to JavaScript:

Time elapsed from project idea to finished library: about 4 hours, during which I also bought and decorated a Christmas tree with family and watched the latest Knives Out movie.

One of his lessons:

If you can reduce a problem to a robust test suite you can set a coding agent loop loose on it with a high degree of confidence that it will eventually succeed. I called this designing the agentic loop a few months ago. I think it’s the key skill to unlocking the potential of LLMs for complex tasks.

Our experience at Thoughtworks backs this up. We’ve been doing a fair bit of work recently in legacy modernization (mainframe and otherwise) using AI to migrate substantial software systems. Having a robust test suite is necessary (but not sufficient) to making this work. I hope to share my colleagues’ experiences on this in the coming months.

But before I leave Willison’s post, I should highlight his final open questions on the legalities, ethics, and effectiveness of all this – they are well-worth contemplating.

Speak Your Mind